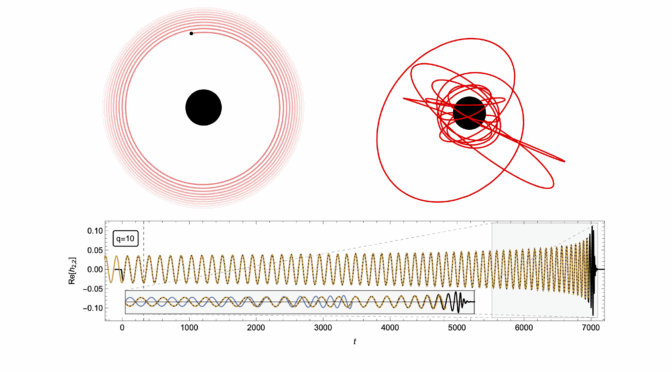

I am delighted to announce that I have been awarded an ERC Advanced Grant. My project, EMRIWaveforms: Waveforms for Extreme Mass Ratio Inspirals, will start in 2026 and will build on an existing proof-of-concept for quasi-circular binaries, developing it into a comprehensive, efficient and accurate waveform model for Extreme Mass Ratio Inspirals (EMRIs) that will be observed by the LISA Mission. #ERCAdG

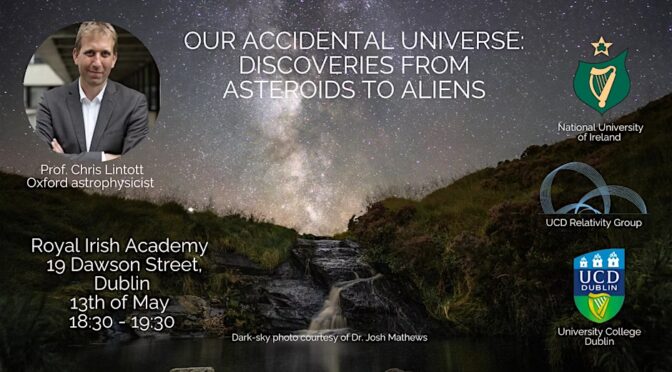

Public astronomy talk by Prof. Chris Lintott

The Relativity Group at University College Dublin is hosting Prof. Chris Lintott to give a public talk at the Royal Irish Academy at 18:30 on Tuesday May 13th 2025:

Our Accidental Universe: Discoveries from Asteroids to Aliens

Many scientific discoveries were made after meticulous planning and examination. But sometimes, the best discoveries happen just by pure luck. Some of them were so astonishing that astrophysicists even contemplated the existence of aliens… or pigeon guano in their instruments. Join us for a tale of cosmic wonders, scientific mysteries, bizarre accidents, and mind-boggling human errors.

The talk will be accessible to a wide audience interested in astronomy and astrophysics. Click here to register for free tickets.

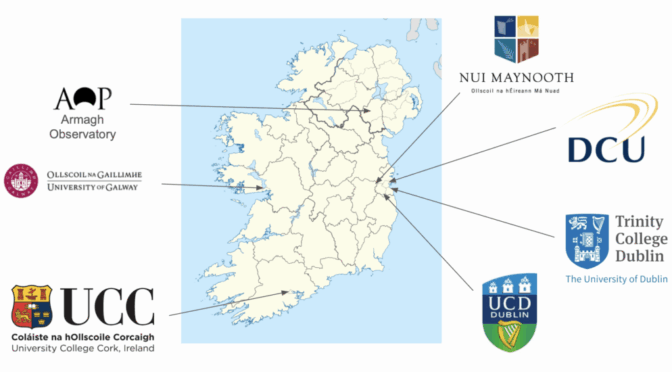

LISA Ireland Meeting

The inaugural LISA Ireland meeting was hosted by University College Dublin and took place on 16th January 2025. The meeting was attended by 25 participants from institutes across the island of Ireland.

15th International LISA Syposium

The 15th International LISA Symposium was hosted by the Relativity Group at University College Dublin on 7th – 12th July 2024. The symposium featured a program dedicated to gravitational wave astrophysics, with particular emphasis on sources that can be observed in the millihertz band by the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), the current status and unique challenges in gravitational theory and analysis for LISA sources, and the latest updates on the development of the LISA mission.

European Einstein Toolkit Meeting

The European Einstein Toolkit Meeting 2022 will be held at University College Dublin from 29 August – 2 September 2022.

The Einstein Toolkit is a community-driven Open Source software platform of core computational tools to advance and support research in relativistic astrophysics and gravitational physics, including Numerical Relativity, studies of Neutron stars and Magnetohydrodynamics.

The first two days of the meeting will include lectures and tutorials geared towards new users of the toolkit. The following three days will focus on the status and future development of the toolkit, including scientific talks as well as dedicated discussion sessions. Participants interested in giving a scientific talk are welcome to submit an abstract during registration. Lectures, tutorials and talks will be presented in-person and broadcasted via Zoom for those who are unable to attend physically.

As part of the meeting there will be a public talk “Exploring the Universe with Gravitational Waves” given by Prof. Alicia Sintes.

25th Capra Meeting on Radiation Reaction in General Relativity

The 25th Capra Meeting on Radiation Reaction in General Relativity was held at University College Dublin, Ireland from 20th – 24th June 2022. The five days were filled with contributed talks and extensive discussion sessions. The conference was held primarily as an in-person event with live remote participation via Zoom.

For more information, see details on the conference website.

Second-order self-force calculation of gravitational binding energy

Nearly 7 years in the making, we have finally finished our first paper describing our second-order gravitational self-force results:

Second-order self-force calculation of gravitational binding energy

Adam Pound, Barry Wardell, Niels Warburton, Jeremy MillerSelf-force theory is the leading method of modeling extreme-mass-ratio inspirals (EMRIs), key sources for the gravitational-wave detector LISA. It is well known that for an accurate EMRI model, second-order self-force effects are critical, but calculations of these effects have been beset by obstacles. In this letter we present the first implementation of a complete scheme for second-order self-force computations, specialized to the case of quasicircular orbits about a Schwarzschild black hole. As a demonstration, we calculate the gravitational binding energy of these binaries.

Check out our paper on arXiv.

Einstein’s Ears: The new astronomy of gravitational waves

Prof. Scott A. Hughes is currently visiting the Relativity group at UCD as part of the university’s visiting professor programme. During his visit, Prof. Hughes will give a public talk on the exciting new science made possible by the advent of gravitational wave astronomy. Prof. Hughes is a highly engaging public speaker and I strongly encourage anyone interested in gravitational waves to addend. Attendance is free but we request that you must register on eventbrite for a ticket if you plan to come.

Dublin School on Gravitational Wave Source Modelling

The Dublin School on Gravitational Wave Source Modelling aims to teach the next generation of gravitational wave researchers the skills they will need for interpreting gravitational wave signals detected by the LISA mission. Further aims are to cover a broad range of topics in gravitational physics, to give newly arrived and early career researchers a chance to interact with each other, and to meet the leaders in their field.

The summer school will be hosted by the School of Mathematics and Statistics at University College Dublin. It will run from 11th to 22nd June 2018, and will consist of ten days of lectures and hands-on workshops, with a weekend off in the middle to explore Dublin and engage in social activities.

There is no registration fee and anyone can participate. However, please do register so that we can ensure that ample space is available for all participants. Participants are expected to cover their own travel and accommodation costs. A limited number of affordable rooms in campus accommodation have been reserved on a first-come first-served basis. There may also be limited student bursaries; if available, these will be announced at a later date.

The summer school is supported by the GWverse COST Action. Students from COST member nations are particularly encouraged to attend.

The Sound of the Universe: detecting gravitational waves in space with LISA

As part of the Irish Quantum Foundations 2017 conference being held at UCD on May 25-26, there will be a public talk by Dr. Enrico Barausse about the exciting prospect of observing gravitational waves in space. Attendance is free but you must register on eventbrite for a ticket.